Photographs by Ken Gerberick, Janis Corrado, and Günter Járl

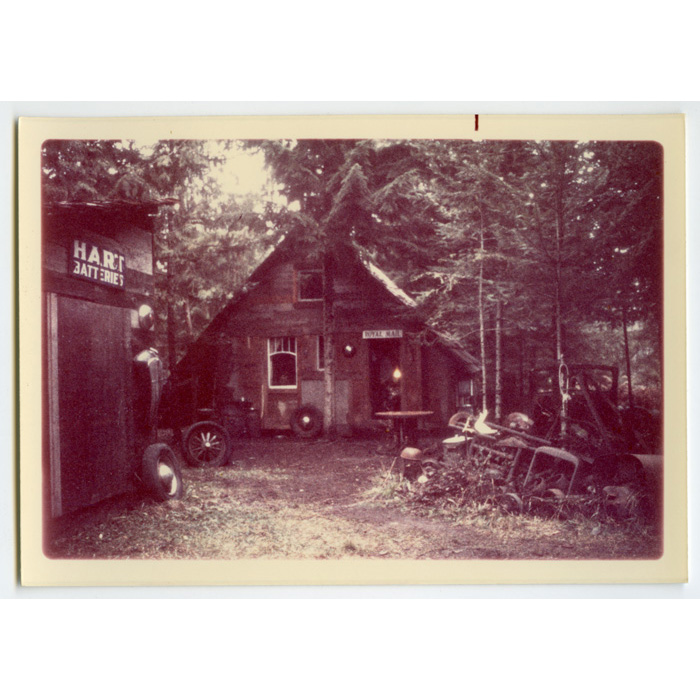

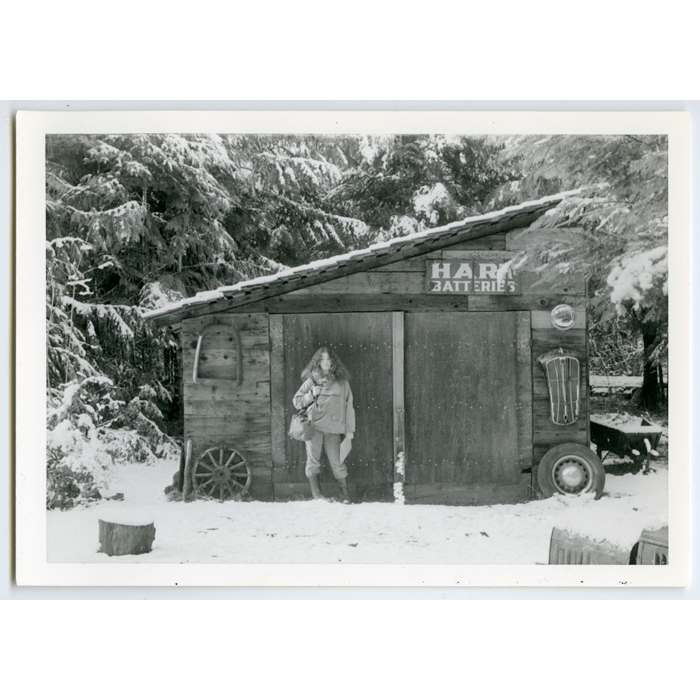

Ken Gerberick: Forest Installation

Alexis Hogan

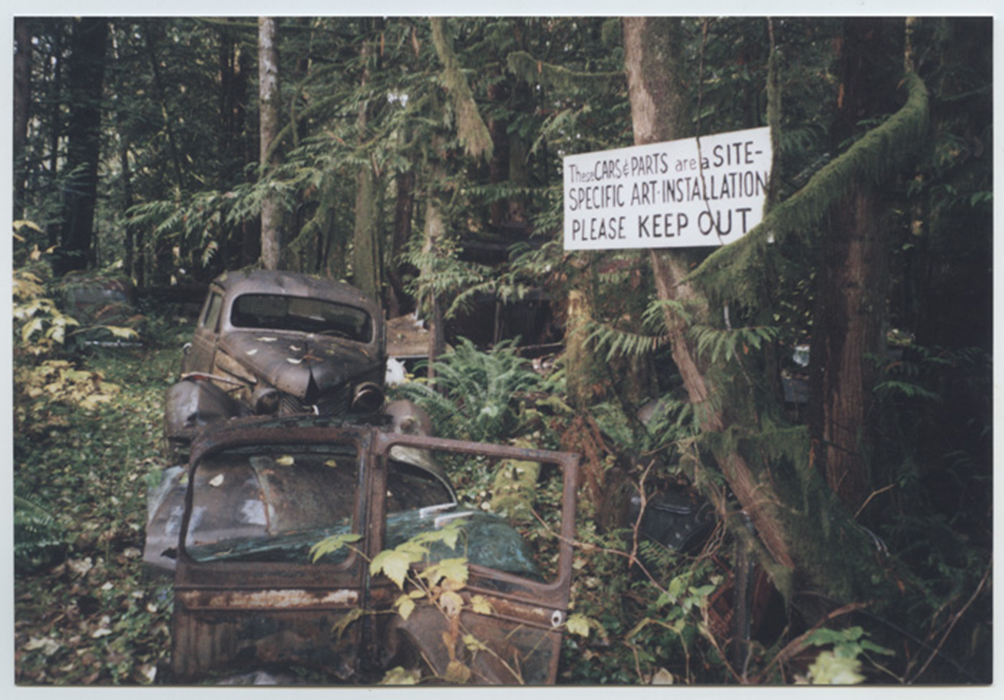

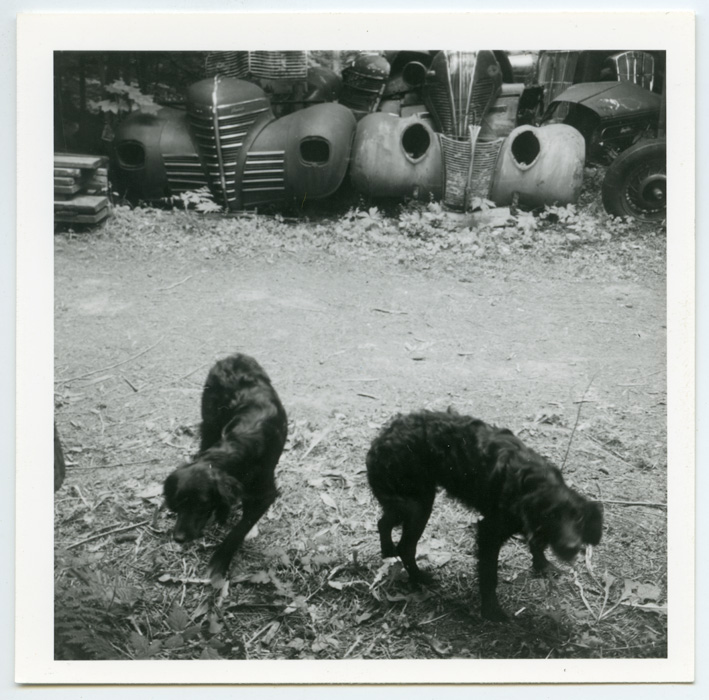

I hike the backwoods often, tracing decommissioned logging roads and trails that vein almost the entire body of Vancouver Island. Among moss-laden undergrowth and towering salmonberry bushes, I’ll stumble over fossils born from nearly two hundred years of resource-hungry industry. It’s not rare to discover whips of steel cable like half-exposed roots, or the rusted forms of abandoned vehicles sunken into beds of coniferous earth, blanketed beneath thick pads of moss. Memories of these encounters with the remnants of lifeless machinery remind me of the site-specific Forest Installation, a project that began in 1970 by Vancouver-based artist Ken Gerberick. Much like deserted cars or homestead sites given over to entropy, Gerberick’s installation of classic American automobiles is a tableau of the forest’s desires to envelop his treasure.

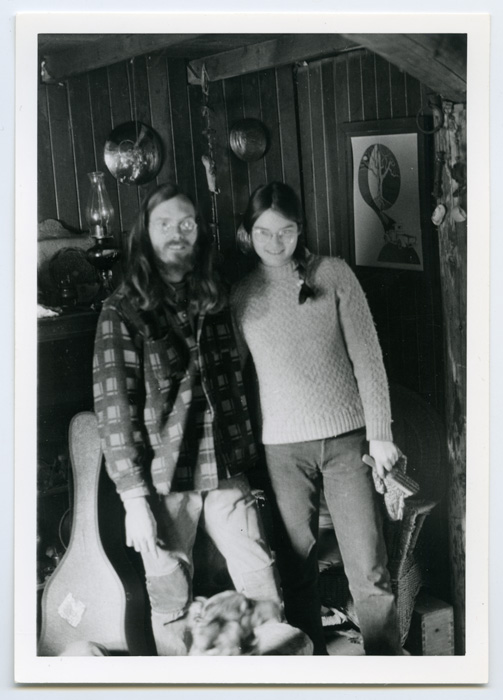

Gerberick is an assemblage and installation artist, originally from Missouri, currently operating out of a studio in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. He came to the unceded and occupied First Nations Territories of what is now called Vancouver Island via an underground railroad for draft dodgers in the late sixties.1 Gerberick deserted the U.S. Army during a training session in Ft. Leonard Wood, Missouri and not long after he made his way up to Vancouver Island by way of California he landed a job as a sign painter.2 If Gerberick hadn’t pursued art as a profession, he would have worked with cars, but he remains convinced he is no great mechanic. Gerberick is distinguished by eccentricities, including a penchant for collecting and a knack for assembling his collections into intricate sculptural works. His practice ranges from large, site-specific installations, to neon sculptures and art cars. Most significantly, he is an individual possessed by a lifelong obsession with automobiles; his fascination with vehicles began early in his childhood but became embedded in his psyche after he witnessed a car accident outside of his parent’s house in Missouri.3 Young Ken ran out to the road and collected pieces of the vehicle’s collision, unaware that spontaneously gathering traces from the incident might spur his affinity for cars and bind it to him. His passion for classic and unique automobiles is a defining feature of his character; throughout his artistic career he has steadily created sanctuaries, be it in his studio, apartment or on a parcel of land, that allow him to be surrounded by relics of the machines that he loves.

Soon after Gerberick secured a ninety-nine year land lease on an undisclosed location somewhere on the island, he began Forest Installation. A constant presence throughout his life in BC, the project distils his love of classic American automobiles and making art. However, due to concerns for both privacy and theft, visiting the property is rare for anyone but Gerberick or his partner Janis Corrado.

In order to navigate the difficulties of experiencing the work in person, Gerberick has created a detailed map of Forest Installation and provided grunt with extensive documentation, both current and archival. He’s shared enough stories with me that I can almost imagine walking through his network of trails, and smell the tang of rotting metal mingling with humus and decomposed logs. Despite earlier deforestation (the land was selectively logged three times before 19704), the forty-six-year-old reliquary is a dense copse of small cedars, whose mossy limbs provide a shady canopy to Forest Installation. The site features one “impermanent structure” (a house built on skids), four sheds, twenty-one antique car bodies, and umpteen cabs and tires. Hundreds if not thousands of American automobile relics line the paths, adorn the sheds and hang all over the house.

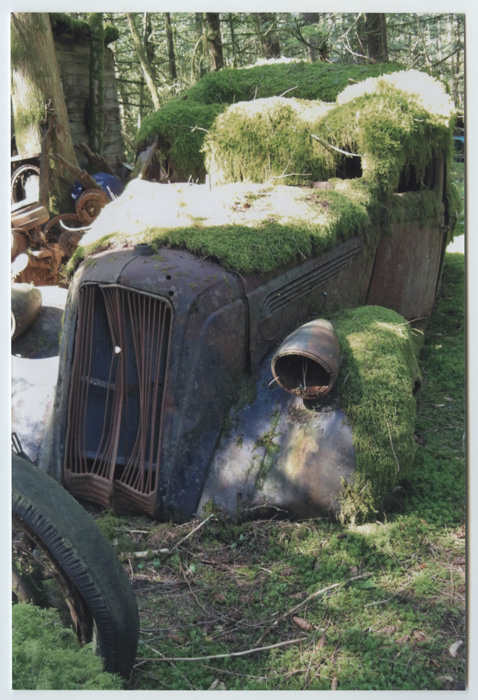

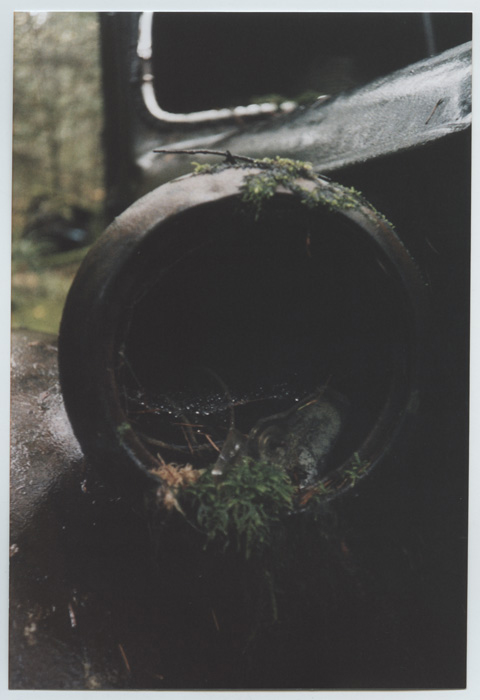

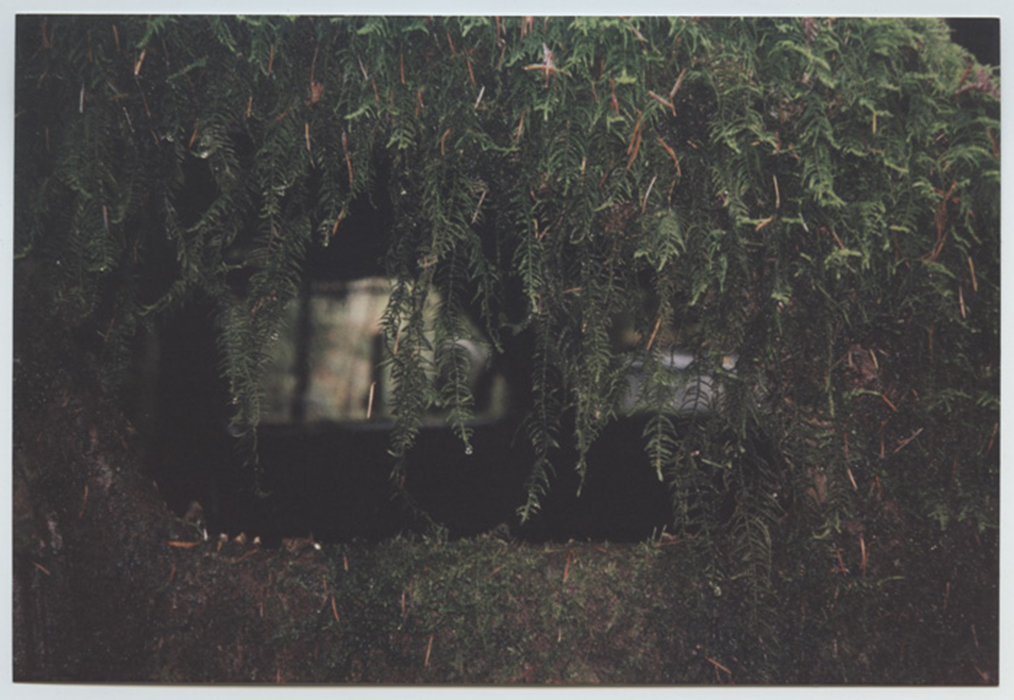

Beyond embodying Gerberick’s two obsessions, Forest Installation is the movement of the slow fingers of the temperate rainforest claiming hoards of automobilia for itself. Nature’s hand competes with the artist’s, transmuting every part that comprises the work. Moss, like rust, never sleeps5: ferns grow, needles scatter, blowdowns crush rooftops and car bodies alike. As the seasons shift Gerberick tends to the site. He discourages leaf litter from piling too heavily against the aging rubber seals of windows; he removes the acidic scales of cedar leaves in order to slow the oxidation of joints, hinges, chrome fenders and hubcaps. His brooms worn down to nubs, the artist scrapes and rearranges plant debris, bringing a sculptural afterlife to the husks of Chevys, Model Ts and Nashs until they nearly hum with nostalgic reverence. Conversely, through non-intervention the artist encourages botanical growth in select areas. Working with and against the forces of nature, he’s created an immersive installation that holds painterly scenes like the one captured in the photograph labelled 2011-2012 Spring 2013 March-July print 32 archive optimized6, where the rounded corners of a ’36 Nash barely nose out of plume moss drapery, exposing iconic swells of wheel-wells and the subdued glint of its once steepled steel grille.

Transformation, the fulcrum concept of Forest Installation, occurs because of the cumulative growth of organisms that come together to create the delicate riparian and woodland ecosystems the installation is located within7. But there are elements of transformation that surround Forest Installation, that deserve further inquiry, like connections between the land his work is beholden to—unceded, occupied, plundered, First Nations territory—and the historical contexts bracketing the era of the automobiles he adores. Inadvertently, a large portion of Gerberick’s collection forms an index of Western economic developments such as assembly lines, mass production and ensuing mass consumption, and also mark the “glory days” of industrial logging practices on Vancouver Island8. Whether they are derelict vehicles left to corrode in the woods or part of a site-specific installation, the automobiles are indexical of a period of Canadian history that strengthened the foothold of capitalist, settler, resource-driven society, which continues to transgress the sovereignties of Indigenous peoples today.

- Julia McKinnell, “A hidden art installation in the B.C. rainforest,” Maclean’s, December 3, 2013, http://www.macleans.ca/society/life/secrets-of-the-forest/

- Ken Gerberick, interview by Alexis Hogan, August 19, 2016, Vancouver, British Columbia.

- Ken Gerberick, interview by Alexis Hogan, August 19, 2016, Vancouver, British Columbia.

- Ken Gerberick, interview by Alexis Hogan, August 19, 2016, Vancouver, British Columbia.

- Neil Young & Crazy Horse, Rust Never Sleeps, Reprise Records, XHS 2295, LP, 1979.

- Ken Gerberick, “Ken_Gerberick_Forest_Installation_2011_2012_Spring_2013_ March_July_print_32_archive_optimized,” Settler Sites, accessed July 15, 2016. Link to image

- British Columbia Ministry of Environment, “Sensitive Ecosystem Inventories: Riparian Ecosystems of Eastern Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands,” accessed August 15, 2016.

- Richard Mackie, “Listening to Loggers: Stump to Dump on Vancouver Island,” accessed August 15, 2016. http://niche-canada.org/2013/07/06/listening-to-loggers-stump-to-dump-on-vancouver-island/

Alexis Hogan (she/her) is a queer white settler with Indigenous heritage (Irish, Quebecois on her mom’s side and Irish and Anishinaabe from Sharbot Lake, Ontario on her dad’s). Her day job is at a community-centred environmental education organization, The Compost Education Centre, which focuses on reducing barriers to accessing education around composting, waste diversion, local food security and ecological restoration and conservation. Her art practice is informed by intersectional feminist, decolonial perspectives. The focus of her practice, through site-specific projects, social practice and printmaking, is confronting settler-colonial extractivism through restoration, reciprocity, reflection and critical care.